By Andrea Reasoner, MD

As May is “Better Hearing and Speech” month, Iowa’s Early Hearing Detection and Intervention Program would like to offer a review of recent updated recommendations. The Joint Committee on Infant Hearing (JCIH)Year 2019 Position Statement: Principles and Guidelines for Early Hearing Detection and Intervention Programswas published in October 2019. It is available for free downloading in its entirety of 44 pages through the following link: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/jehdi/vol4/iss2/. Since the scope of the Position Statement is broad, including recommendations for all pertinent specialists, the goal of this article is to share information most pertinent to the primary care provider.

“Fail” is the new “refer.”Previously “refer” was the preferred way of stating a child “did not pass” a hearing screen. However, the term “refer” is confusing, and has been replaced with “fail.” A fail is given if a child does not pass in one or both ears.

“Hearing loss” is differentiated from“hearing thresholds outside the typical (normal) range.”A newborn who has deafness or is hard of hearing, has not “lost” hearing. However, a child identified with a progressive or late onset condition of deafness or hearing impairment has lost hearing.

How are we doing with the 1-3-6 Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) Goals?

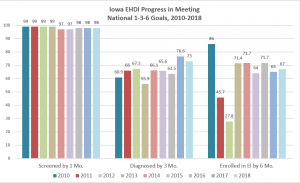

The EHDI goals for care include that a child should receive his first hearing screen by 1 month of age, a diagnosis of hearing loss by no later than 3 months of age, and initiation of early intervention services by 6 months of age.

The nation is doing well with meeting the first EHDI goal of newborn hearing screening by 1 month of age. However, we still struggle with getting those infants who failed their initial screen diagnosed by 3 months. Factors include babies born at home, rural areas lacking in services or equipment, and more importantly providers not moving infants along in a timely manner. Some doctors are not aware that a screen performed in the medical home needs to be reported in the EHDI database, as required by law.

For purposes of clarification, the actual diagnosis of hearing impairment is made by the audiologist, who then immediately refers to Otolaryngology so a cause can be determined, and medical and/or surgical treatment can be rendered. The audiologist can fit the child for hearing aids if appropriate. Early developmental intervention should be started as soon as possible after diagnosis, so language acquisition is not delayed. The timeliness of intervention is so important that the goals are changing to 1-2-3-month timeline(screening completed by 1 month, audiologic diagnosis by 2 months, enrollment in early intervention by 3 months) for those states who currently meet the 1-3-6 benchmark.

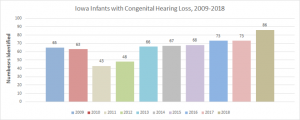

How many Iowa children with hearing loss are identified during infancy?

We are identifying more and more infants with hearing loss as noted in the graph below. In 2018, we identified 86 children with congenital hearing loss or 2.3/1000. Another 2-3% will be identified with late onset or progressive hearing loss. This magnifies the importance of moving children along from screening to re-screening, and ultimately to a timely diagnostic assessment.

We need to do better with getting the children diagnosed and referred to early intervention in a timely manner.

Iowa EHDI ‘s last set (2018) of 1-3-6 outcomes data shows nearly complete success with screening newborns by one month, but only about 3/4 of those newborns with a failed screen are diagnosed by 3 months, and only about 2/3 of those diagnosed with hearing impairment are enrolled in early intervention by 6 months.(See Figure 1)

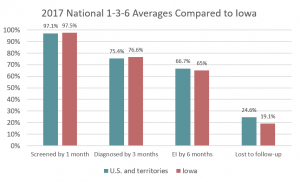

The 2017 Iowa data shows similar outcomes for the 1-3-6-month goals compared with the National averages. However, Iowa is doing even better than the nation in “lost to follow up” with fewer infants being lost to follow up after birth or after failed screens. (See Figure 2)

Figure 1:

What has changed with newborn screening recommendations?

It is now acceptable to use Otoacoustic Emissions (OAE) to rescreen an infant who fails an Automated Auditory Brainstem Response (AABR) screen, but only in the newborn nursery. This is due to the very low incidence of auditory neuropathy in newborns discharged from the nursery as compared to the NICU. For this reason, for an infant in the newborn nursery, a pass on either OAEs or AABR is acceptable, if both ears passed in the same screening session. This pattern of screening would not be acceptable in NICU infants given the higher incidence of hearing loss and auditory neuropathy. A child with auditory neuropathy will often fail the AABR, then pass the OAE. For this reason, the screening recommendation for NICU infants is to only use the AABR. NICU infants who fail the AABR should be referred immediately to an audiologist for rescreening or diagnostic testing. When possible, infants should be diagnosed by an audiologist prior to hospital discharge from the NICU. Babies with severe ear malformations or stenosis of ear canals should skip the hearing screening and be referred immediately to an audiologist for a diagnostic hearing evaluation.

All hearing screen results need to be reported to the state EHDI program.

If standard screening equipment (OAEs or AABR) is not available at the birthing hospital, or if the baby is birthed at home, the screen may occur at the primary care provider’s (PCP) office. It is important that we understand behavioral responses to a whispered sound or noisemaker do not qualify as adequate screening. Otoacoustic and AABR equipment in the office setting requires calibration by trained professionals, and the hearing screen program requires audiology oversight. If OAE screening is not available in the PCP office, a referral should be made immediately to ensure the infant is screened before one month of age. If an infant is screened in the office, the PCP is responsible for reporting the results to the EHDI program.

What can we do about infants lost to follow-up and undocumented results?

Certain situations place a baby at risk of getting lost to follow-up or lost to documentation in the Universal Newborn Hearing Screening system. These are 1) when babies are born at home or in other locations out of hospital where there is no screening equipment, 2) when babies are born across state borders where there are separate EHDI databases, 3) when infants are discharged from the hospital before a screen is done, and 4) when a baby is transferred to another hospital either in-state or out-of-state. In all these situations, systems need to be put into place to assure that screening is done as recommended within the EHDI 1-3-6 goals, and that the results are shared between providers and databases. These systems may include phone notifications to families, written agreements between providers and hospitals, and reminders in transfer notes.

PCP should monitor middle ear status

As a newborn, retained amniotic fluid or persistent middle ear effusion (MEE) can delay or confuse the diagnosis of hearing loss. Management of MEE and associated conductive hearing loss should be coordinated by the PCP with referral to Otolaryngology following diagnosis or input from the infant’s audiologist. Tympanostomy tubes may be indicated. Conductive hearing loss has causes other than just MEE, which may require more extensive evaluation with bone and air conduction tests and radiographs.

What follow-up is needed for newborns who pass the hearing screen?

Every newborn should be assessed for risk factors associated with early childhood hearing loss. These factors include family history of permanent or progressive childhood hearing loss, craniofacial anomalies, and administration of ototoxic medications in the NICU for >5days (see table 1 for complete list). If no risk factors are identified, the infant should receive ongoing surveillance of communication development starting at 2 months of age and continuing into childhood as recommended in the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Periodicity Schedule. Prevalence of confirmed deafness/hard of hearing is 1.79/1000 in the neonatal period and 3.65/1000 by school age. This increase represents not only children with delayed onset or progressive hearing loss, but also likely includes some children who had minimal or mild hearing impairment at birth. This gap is because otoacoustic emissions used in infants may not identify those with mildly elevated hearing thresholds of 25 to 40 db.

The risk factors for delayed onset hearing loss are now organized differently. Previously there were several factors that required follow up evaluation of hearing by 6 months, and another several that required follow up by 24-30 months. Now, there are 12 risk factors, separated into 2 groups: predominantly perinatal factors, and factors that could be perinatal or postnatal. Also, the follow up period is now by 9 months of age; this represents a closer follow-up for most cases. Other situations should have follow-up no later than 3 months after occurrence; this includes ECMO, congenital CMV, culture-positive infections associated with SNHL, and events (head trauma/skull fracture, chemotherapy) associated with hearing loss. Infants with possible prenatal Zika exposure, suspected or confirmed Zika syndrome, should have a standard screening at birth, and an AABR by age 1 month if the newborn screen was passed using OAE.

Congenital CMV deserves special mention as a leading cause of progressive, delayed onset hearing loss. It occurs in 0.2 to 2% of live births internationally. Antiviral treatment with ganciclovir, though still being studied, shows protection against hearing deterioration caused by CMV; however, concerns remain about its possible toxicity.

With more than 400 syndromes and genetic disorders associated with hearing impairment (or atypical hearing thresholds), their presence is a risk factor. A family history of childhood onset hearing loss is a risk factor given the possible genetic nature. At least fifty percent of the causes related to being deaf or hard of hearing are hereditary. Therefore, a genetics evaluation is important when looking for a cause of hearing impairment, with genetic testing and genetic counseling being offered to the family. This testing is typically done in coordination with the Otolaryngology team’s evaluation and care for the affected child.

Caregiver concern about speech/language development, developmental regression, or hearing requires immediate referral for hearing evaluation.

Please review Table 1 from the Position Statement paper for a complete list of risk factors and their diagnostic follow up recommendations:

Hearing amplification

Hearing can be amplified using hearing aids, cochlear implants, bone conduction hearing devices, and assistive hearing technologies. A child over 1 year of age with bilateral severe to profound SNHL who does not make expected progress with hearing aids should be considered for cochlear implants. Regular assessment of hearing status and amplification devices by a skilled audiologist in coordination with otolaryngology for ear health optimizes auditory development which is critical for spoken language development.

Support Systems

The impact of social determinants of health is ever increasing. The importance of building connections with family support groups, deaf communities or individuals, early intervention services, spoken language and/or sign language instructors, family service coordinators, and counseling services cannot be understated.To make a referral for early intervention services, following parental consent, please contact the Iowa Family Support Network by calling 1-888-425-4371 or through their website, https://www.iafamilysupportnetwork.org/. To make a referral for family-to-family support, please call ASK Resource Center at 1-800-450-8667.